Part 3: The Problem with Oranges

In a previous blog entitled “Distinguishing Apples and Oranges”, I described the distinction between two separate sets of assessment practices:

Formative assessments that invite a student to participate in a series of learning experiences, all the while giving them the resources and constructive feedback to increase their ability and\or understanding within a particular domains (Apples)

Summative assessments that are designed precisely to generate rank-ordered comparisons of apparent student achievement (Oranges)

I then rhetorically asked what is wrong with using both apples and oranges in our assessment of students at school? Put differently, isn’t it intuitively obvious that we use certain (formative) assessment practices to try and figure out what students know and can do (i.e. so we can further extend their learning), and then later give a (summative) account of what they have apparently learned? Doesn’t it make sense, in the case of the latter, that we render student achievement in terms of something like rank-order percentages or grades?

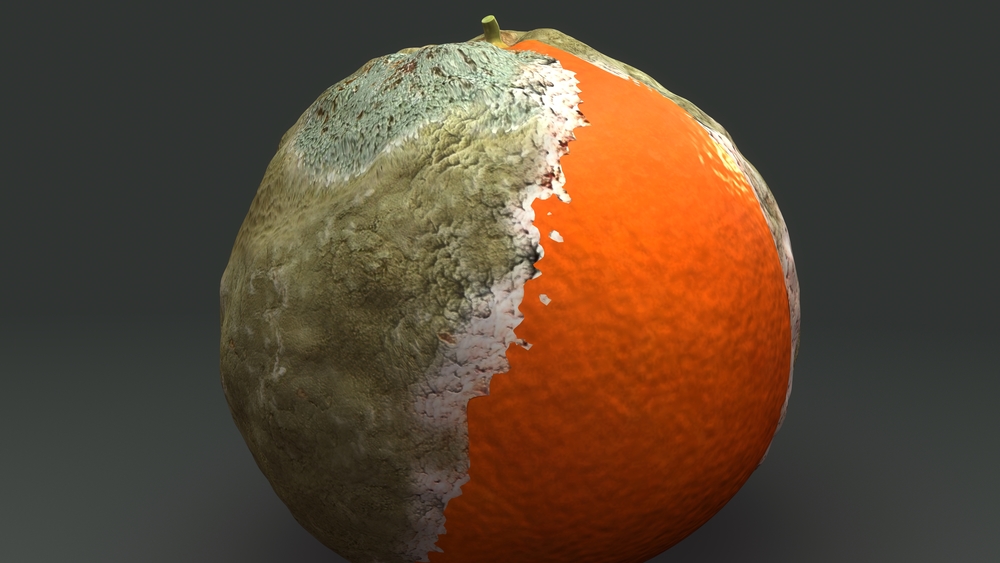

The problem is that the summative characterization of student achievement, as expressed in terms of rank-ordered grades, actually dominates and shapes the entire assessment environment of contemporary schools. In so doing, it threatens the quality and integrity of the educative project as a whole in at least five different ways. In this blog and the three that follow, I will describe each of these threats separately.

First, an assessment system that is ultimately aimed at generating a rank-ordered descriptions of student achievement will almost necessarily tend toward instructional practices that narrow, fragment and trivialize the subject matter under study. Consider, for example, the teaching of poetry in schools. Imagine that we want to introduce students to the world of poetry as a human accomplishment that is worthy of our attention, and perhaps even of a lifelong interest. To make this introduction we are likely going to give students examples of poems to examine, point out a few techniques that are employed, and (hopefully) have them write some poems of their own.

Now consider how we typically assess a student’s “understanding” of poetry? By focusing on the least important, most peripheral (but most easily measurable) elements of the practice. English teachers the world over make students memorize the definitions of metaphor, simile, allusion, onomatopoeia, etc. and then happily grade them on their understanding of poetry on the basis of being able to properly identify these techniques in use. We do this because it is much easier to get an “objective” measure of student “understanding” by creating right\wrong questions on a test that will yield a definitive quantitative result (i.e. 3/10, 6/10, 10/10 etc.).

As it is with poetry, so is it with so many other things in school. The beauty of mathematics gets reduced to formulae that need to be memorized; history becomes little more than a series of dates to regurgitate; science is encapsulated as a list of components to be identified on a cell diagram; French is diluted into the successful recital of verb conjugations; and expressing important ideas on paper never gets above or beyond is a matter of following a preset essay form. Years of educational research and on-the-ground teaching experience confirm that “teaching to the test” necessarily diminishes the investigation under study. The first casualty of a summative assessment regime -- one that privileges oranges over apples -- is a deep and rich introduction to the world of ideas.

Dr. Ted Spear has over 25 years of teaching and administrative experience in public and independent schools. In July, 2019 he published a book about the future of education entitled, Education Reimagined: The Schools Our Children Need. He is an engaging speaker who invites parents and educators to change the way we think about schools.